Why you should use a Read-It-Later App

How a read-later app can help you with your digital readings.

Photo by Gabriel Sollmann on Unsplash

We live in a world of constantly divided attention. Access to the communications technologies of the 20th and 21st centuries has brought many people to a point where they can potentially be absolutely inundated with information of wildly varying relevance. If you want, you can spend all day just watching the latest moves in various power plays that you can’t affect, and not even begin to see things that could be actually useful to you, personally. There are arguments as to what degree the world is getting weirder, and to what degree we can just see it better because of the internet. Regardless, though, the world we experience, through our screens, is definitely broader than that of an average person even 30 years ago.

Microsoft researcher Linda Stone describes one result of this situation as “Continuous partial Attention”

Continuous partial attention is an always on, anywhere, anytime, any place behavior that creates an artificial sense of crisis. We are always in high alert. We are demanding multiple cognitively complex actions from ourselves. We are reaching to keep a top priority in focus, while, at the same time, scanning the periphery to see if we are missing other opportunities. If we are, our very fickle attention shifts focus. What’s ringing? Who is it? How many emails? What’s on my list? What time is it in Bangalore?

In this state of always-on crisis, our adrenalized “fight or flight” mechanism kicks in. This is great when we’re being chased by tigers. How many of those 500 emails a day is a TIGER? How many are flies? Is everything an emergency? Our way of using the current set of technologies would have us believe it is.

How do we achieve stability under these conditions? By encouraging what author and theologian Alan Jacobs in his book Breaking Bread with the Dead calls “[Personal Density]((https://blog.ayjay.org/how-change-happens/)” As Zachary A. Howard summarizes it:

“Jacobs argues that increasing personal density is important because our current “environment of high informational density produces people of low personal density” (p. 150). Personal density is directly proportional to “temporal bandwidth,” which Jacobs defines as “the width of your present, your now…. The more you dwell in the past and in the future, the thicker your bandwidth” (p. 19, original emphasis). Thus, a person with high personal density is not tossed to and fro by every wave of crisis in the news nor blown around by every wind of outrage from the Twitterverse. Personal density is a specific kind of mental maturity developed through fellowship with the past.”

And how do we gain this density? Jacobs suggests that one of the best ways of doing so is by reading, specifically by reading at length and at depth. The emphasis that Jacobs makes is on works that have stood the test of time, but he also makes clear that long-form reading in general, as opposed to a constant input of fragmentary thoughts, will improve a sense of personal stability.

The internet is optimized right now for short form, high saturation, low-density input. The way to get around that is to be selective in what, and when, you read, so that you not only choose wisely what to take in, but you do so when you have the attention available to dedicate to it.

Read Later apps

One of the most effective ways to do this is by using a Read Later app. Read Later apps allow you to acquire long-form content that you might not have time or bandwidth to digest immediately, and read it later at your leisure. This means that you can choose to read things of more depth than the latest Scandal Du Jour, things that do not require an immediate emotional response nor demand you to waste your time responding and contributing to the noise that surrounds us.

Choosing the time and space in which to read also improves your comprehension. Saving a long-form piece to a Read Later App means that when someone sends you a link to an article while you’re focused on work, you don’t have to make the choice between breaking your focus time and reading; you can easily wait until you can dedicate your full time and attention to reading, thus ensuring that you are able to more fully process and understand the piece. And even if you can’t dedicate time to reading, having a single long-form piece available to you in a way that preserves your progress means that in the fragments of time, you spend waiting in line or commuting, you can eventually digest something worth digesting, and not the intellectual equivalent of high sugar snacks.

Sometimes the blocker isn’t time, but understanding. If a piece is complex or made up of many parts, often it can be challenging to process it all at once. If you are using an app that saves your place, you can easily take a break, perhaps even take a walk to think about what you’ve just read, taking the time to fully integrate one set of ideas before moving on, without having to worry about a browser crashing, or a tab reloading to a random place in the article.

Read Later with Omnivore

There are a number of Read Later apps on the market, but we’ve built Omnivore to be optimized for ease of getting items into it, so you can take full advantage of the ability to pick when and what you read. So how do you get things to read later into Omnivore?

The easiest way for most people is the browser extension. Available in the Chrome Store, Safari, Edge, and Firefox Add-Ons Directory, the extension makes it easy to add most web pages or PDFs online into your Omnivore library.

(caption: The Chrome extension after adding an article)

With one click, a page is added to your library, so you can access it at any time. The interface also allows you to add notes, if you have an immediate thought or insight, or perhaps a summary that will be helpful in choosing what to read at a later time. Labels are also useful for sorting your library later. I often add labels corresponding to a project the article is related to, if I am collecting resources for research purposes. Other people find it useful to add labels for estimated time to read, so they can pick something for whatever length of time they have available. For more on using and searching for labels, see this article.

What if someone sends you a link via text on your phone? No problem, the mobile version of Omnivore on both Android and iOS allows easy sharing to Omnivore from your mobile browser.

(caption: Sharing to Omnivore on iOS)

The interface on iOS also allows for immediate adding of labels and notes, so you can easily find things later in your library (this feature is still in development for Android, but will be coming soon).

Omnivore also allows subscribing to RSS feeds and newsletters (see this article for details on both), meaning that, wherever you get your long-form content, it’s easy to have it all in one place, where you can pick and choose what you want to engage with on your terms, at your time.

To get more of an overview on how to save anything to Omnivore, check out this article.

Reading in Omnivore

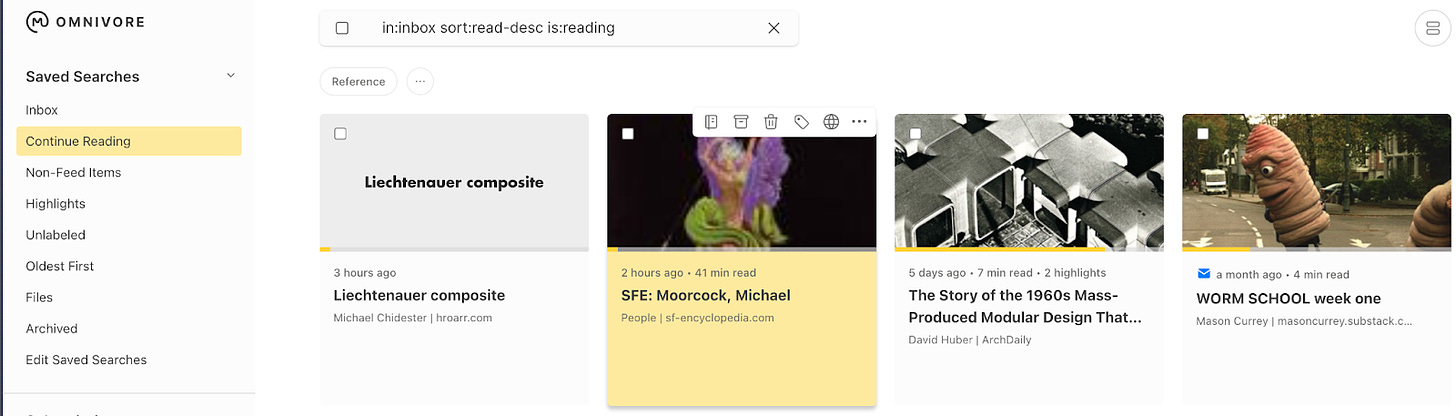

(caption: An Omnivore library showing a PDF, two web pages, and a newsletter)

The Omnivore Library shows everything you have saved in one place. The search box can be used to find items based on labels (either those you have added manually or those added automatically by Omnivore based on source type or rules defined by you) or the text of saved items (for more information on searching, see this article). This allows you to quickly find something appropriate for your current time and attention availability, or just your mood.

A significant amount of research has indicated that the most effective way of engaging with a text for comprehension is to take notes on it as you go. Omnivore has built-in highlighting and notes, so you can read with pen in hand, as it were while keeping your thoughts connected to the document automatically. Omnivore has plugins available for both Obsidian and Logseq that will automatically sync your notes to those platforms, so you can easily integrate them into whatever workflow you prefer.

Omnivore will preserve your last-read location, so you can easily take a break and come back to an article knowing that you can pick up where you last left off. The library even shows progress bars on your items, so you can get a sense of how much more time you need for each of them. And items sync automatically, so you can easily move between reading on your mobile during a commute and with a tablet when you are sitting at home.

Add to this that Omnivore is free, open source, in active development, and offers a self-hosted option if you want full control over your data, and it becomes a fantastic choice for maximizing focus, attention, and comprehension for all of your electronic reading.

Conclusion

The world is increasingly driven by an attention economy that demands that everything in your field of perception is The Most Important Thing that you should pay attention to right now. When everything around you claims to be more important than everything else (to paraphrase philosopher Lemmy Kilmister) this leads to a situation wherein there is so much overhead to deciding what to read that it wastes time that we could be using to actually read.

A Read Later app can help you manage this information overload, and let you tame the constant influx of new data, allowing you to take control of when, where, and how you read any given thing. Assigning your own priorities, rather than letting them be assigned for you and being blown about by the winds of a fickle market, gives you a power of conscious application of attention, which, in turn, gives you an edge over all those who let their attention be directed by others.

To put it another way, using a Read Later app allows you, in the words of Marcus Aurelius, “To read with diligence; not to rest satisfied with a light and superficial knowledge, nor quickly to assent to things commonly spoken”.

Written by Steen Comer.

I love Omnivore, but wish so much it supported book highlights (from kobo/kindle). At the moment I have to use both Omnivore and Readwise (both syncing with Obsidian).